Overview

For my master’s thesis at TU Berlin, I developed a complete pipeline that transforms robot-scanned 3D data into a functional neural network for indoor localization. The system eliminates the need for manual data collection by training exclusively on synthetic images, achieving practical accuracy on a real-world office building dataset.

Background

Indoor localization is fundamental to many applications, from assistive navigation for people with visual impairments to augmented reality experiences. While GPS works great outdoors, it fails indoors due to signal reflections and building materials blocking satellite signals. Traditional approaches like WiFi fingerprinting or visual markers work, but they either lack accuracy or require extensive infrastructure installation.

Neural networks offer a promising new path, using just a device camera to determine precise location and orientation.

The challenge here is data collection, as networks need thousands of pose-annotated training images to function properly. Collecting this data manually is time-consuming and prone to gaps that may not be obvious until after the network is put into use.

Another open question is how well localization networks can perform in large, self-similar environments, like the corridors of an office building. Most existing research focuses on smaller, more distinctive spaces, leaving real-world scalability unproven.

My thesis addresses both challenges: building an end-to-end pipeline that generates synthetic training data from existing robot scans (specifically LIDAR point clouds and 360° images captured during routine mapping), while also validating whether this approach actually works at scale in a large office environment.

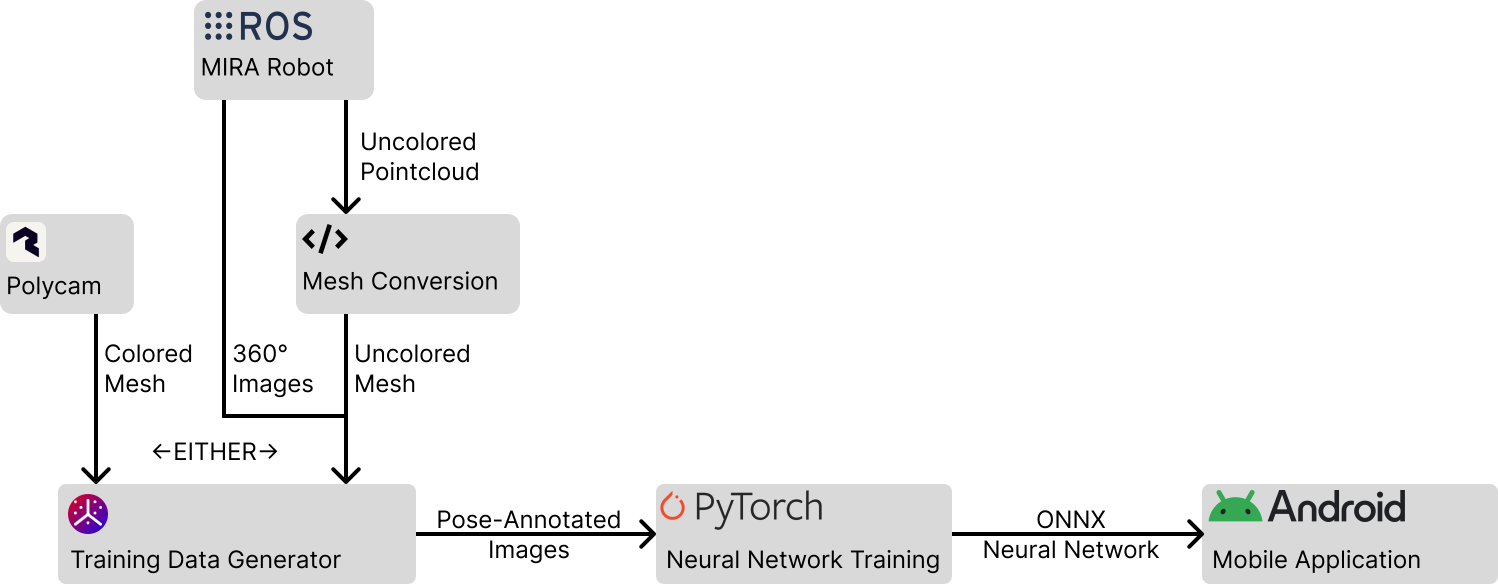

The Pipeline

The system consists of three main components that turn uncolored point cloud and 360° image data into a 6DOF relocalization network:

- Mesh Reconstruction

- Clean up the data from the LIDAR scan, turn it into a mesh

- Synthetic Data Generation

- Create Pose-annotated training images in a user-defined distribution

- Neural Network Training

- Create the final neural network from the training images

1. Mesh Reconstruction

The first step converts LIDAR point cloud data into a solid 3D mesh. I evaluated two reconstruction approaches:

Ball Pivoting Algorithm (BPA) works like rolling a ball over the point cloud, connecting points when the ball touches them. While intuitive, it struggled with the noise in our dataset, producing rough surfaces even with multiple passes at different ball radii.

Poisson Surface Reconstruction approaches the problem differently, treating it as an optimization to find a smooth surface that best fits the measured points. This proved much more effective for our data. After experimenting with different depth parameters (9-11) and smoothing values, a depth of 10 with minimal smoothing provided the best balance between detail preservation and noise reduction.

A key preprocessing step was clamping points to the floor level, since the robot scans often included erroneous points below the actual floor. I also implemented surface extrusion to fix inconsistent face orientations in the mesh, ensuring proper rendering from all viewpoints.

2. Synthetic Data Generation Tool

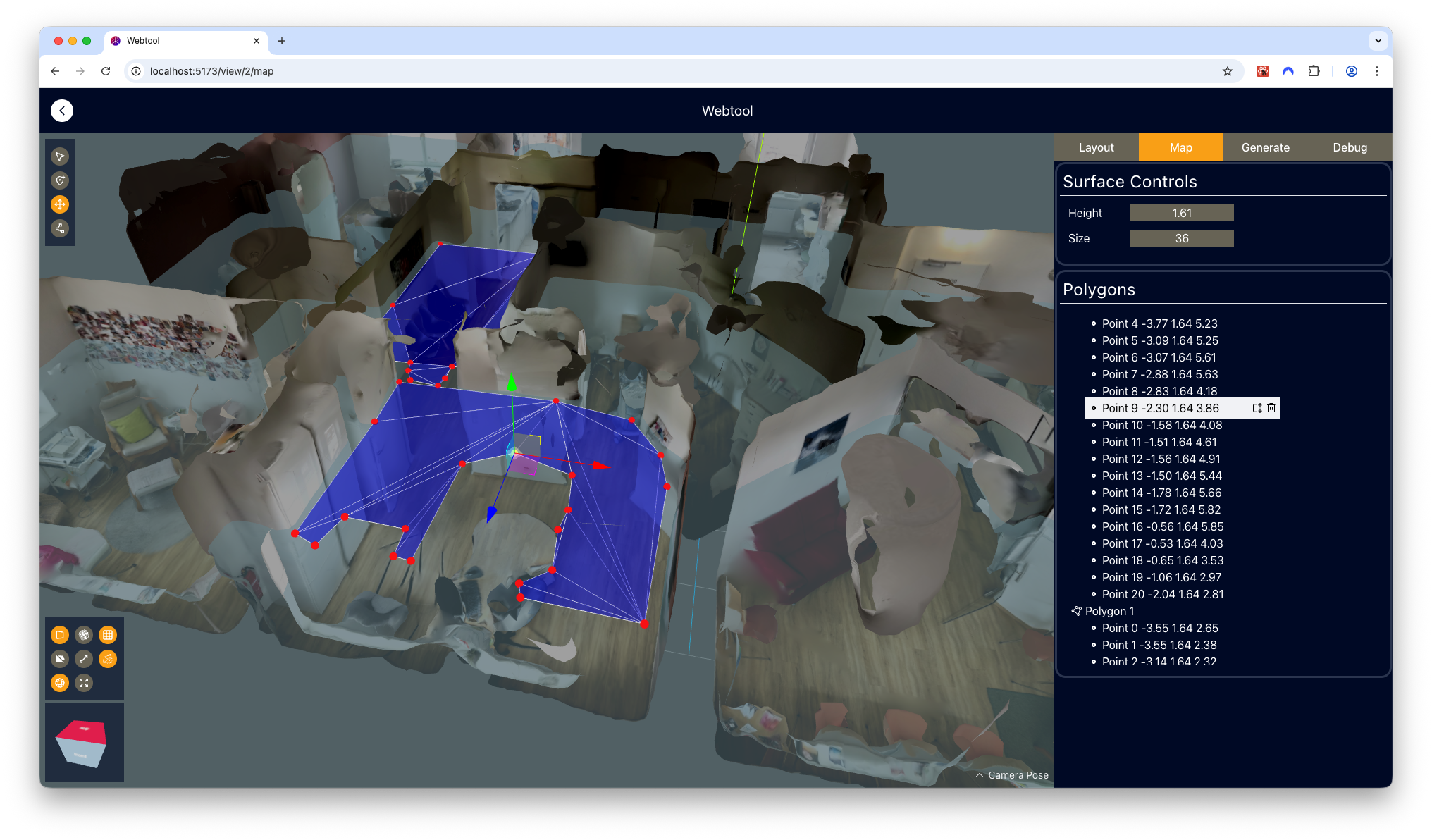

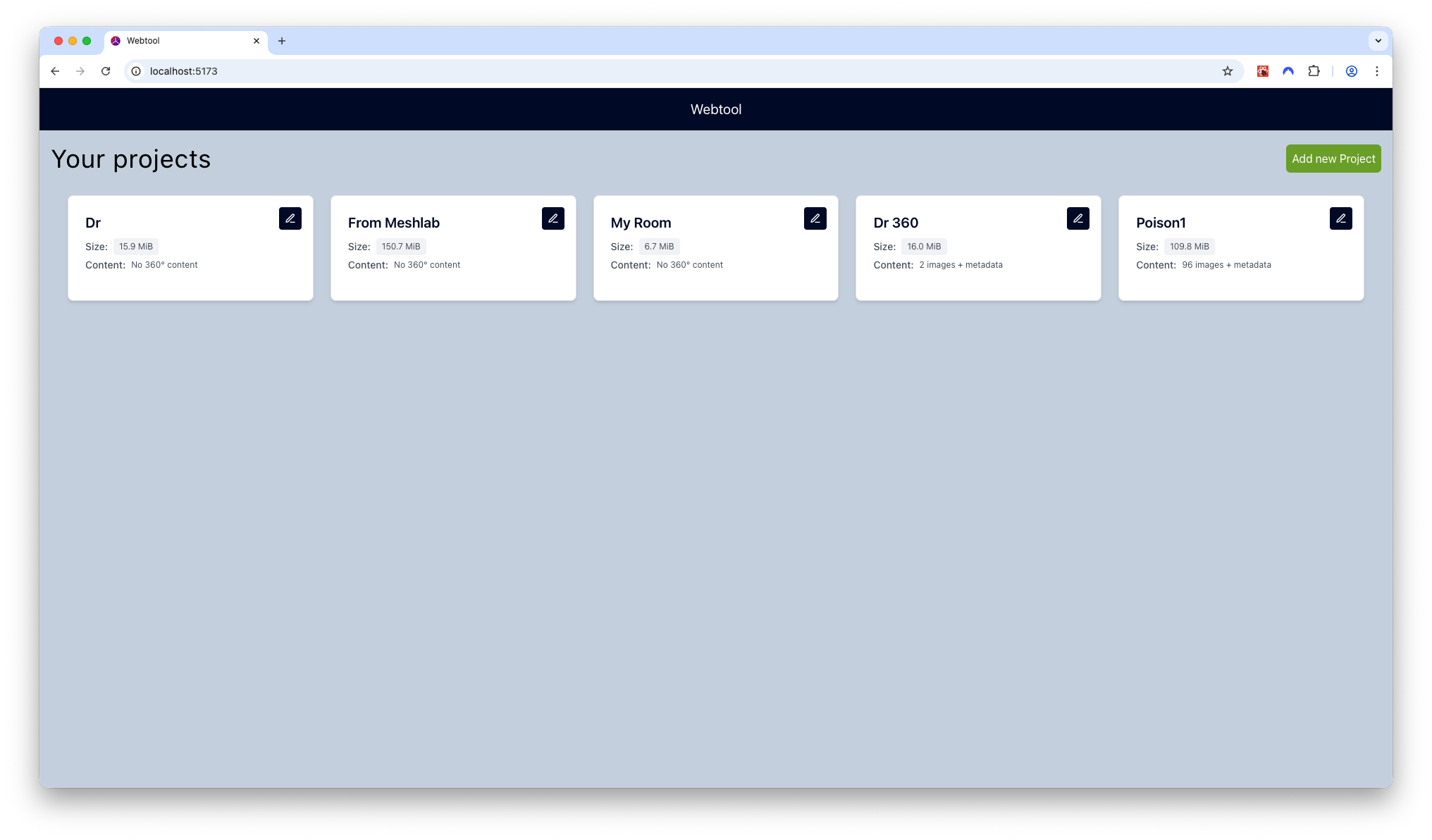

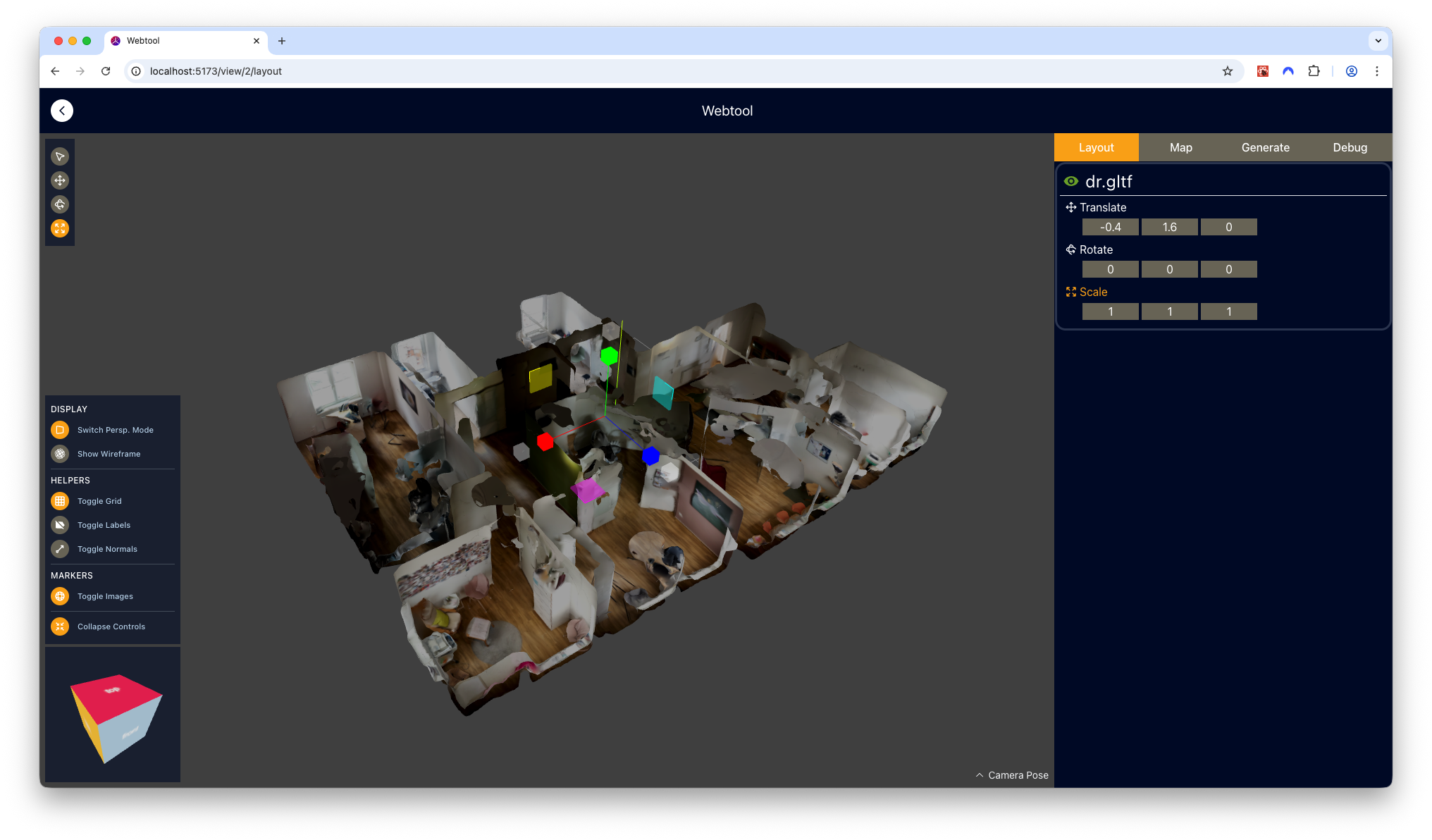

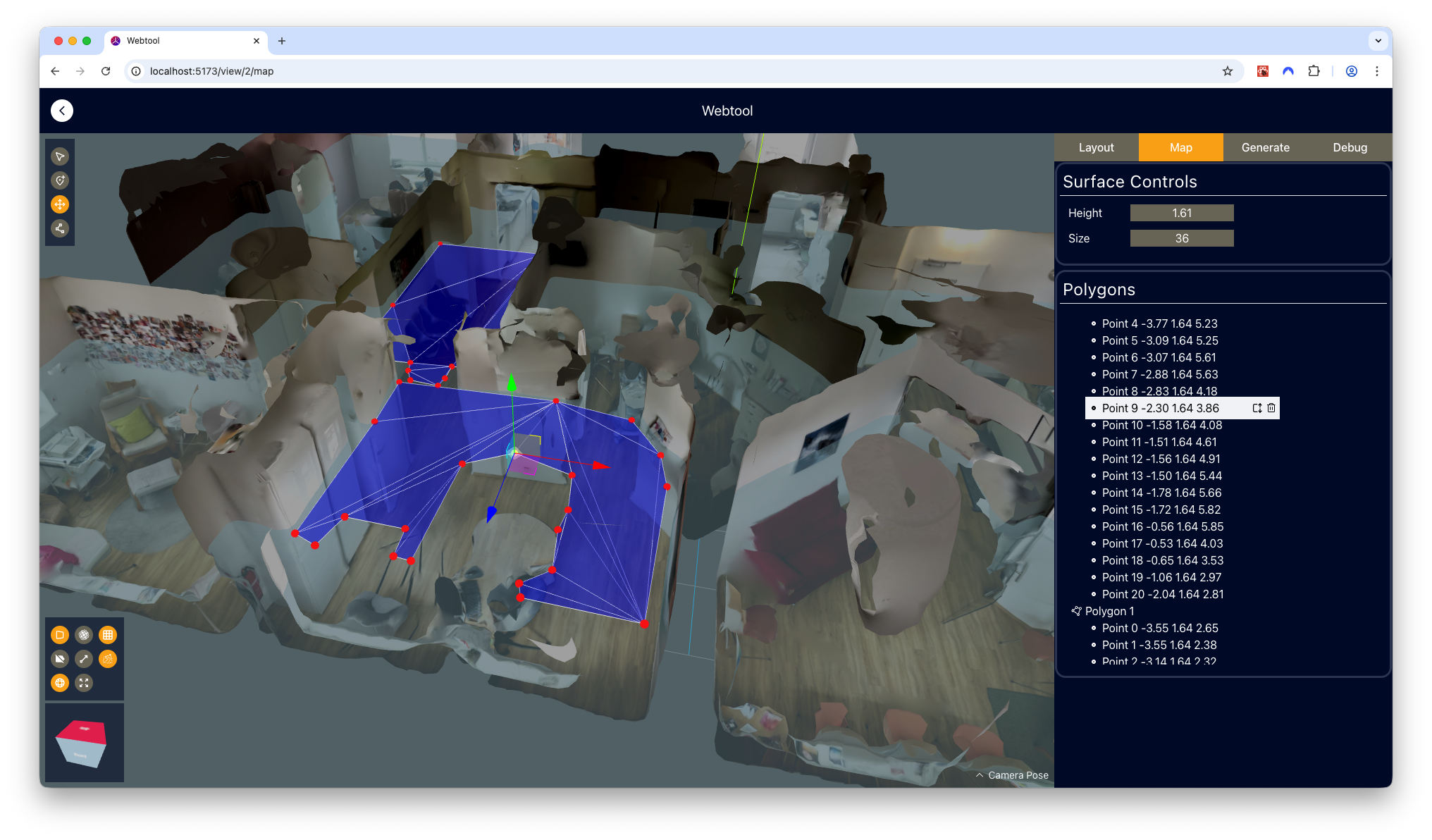

After the comparatively small data reconstruction step, a web-based tool is used to generate training images from the reconstructed mesh, along with 360° images.

The tool guides the user through a 4-step workflow. They

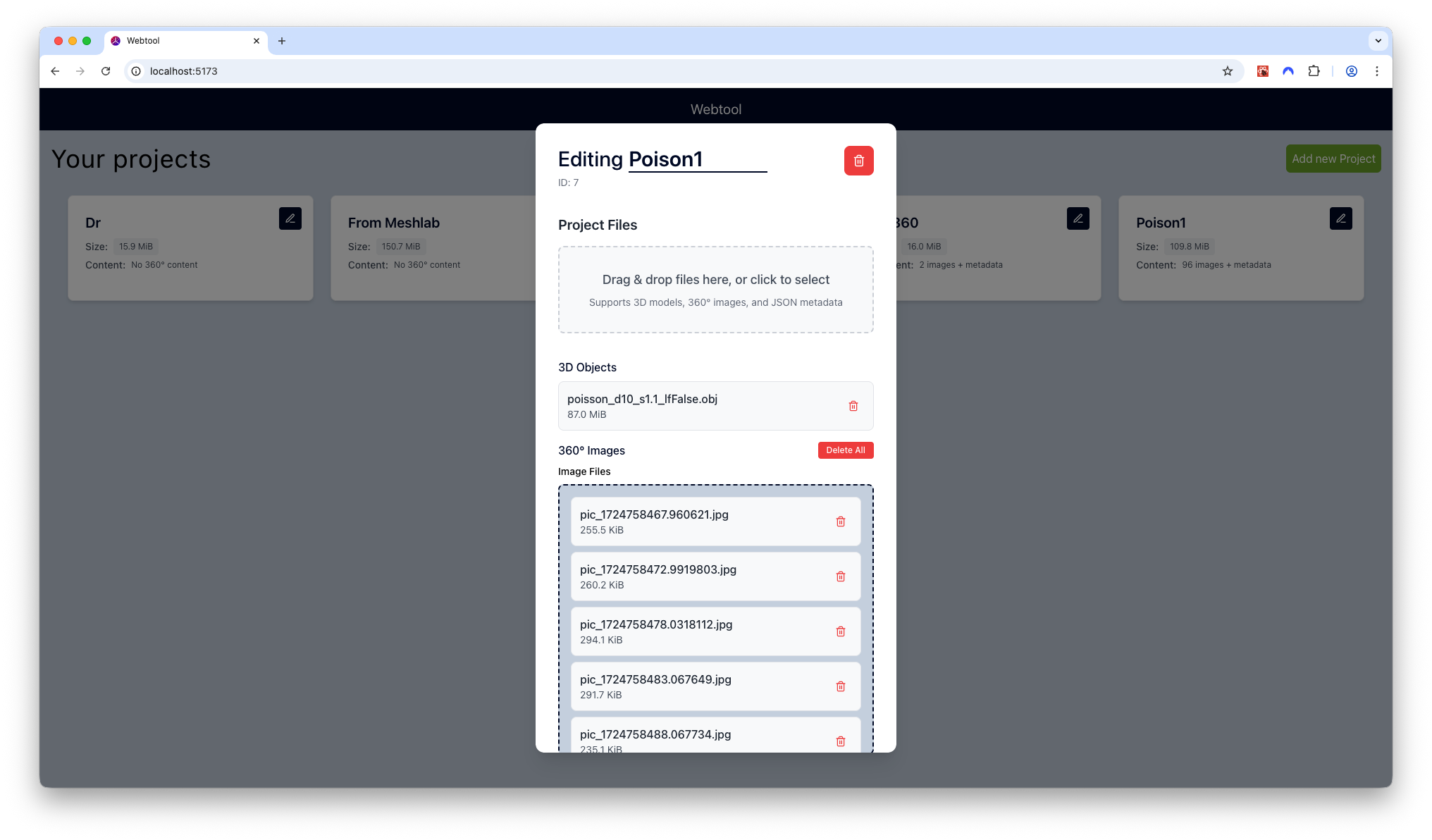

- Create the project and upload model and image files

- Check the relative positioning of imported assets for correctness

- Define volumes in 3D space where synthetic training images should be generated

- Specify export and texturing parameters, and download the final images

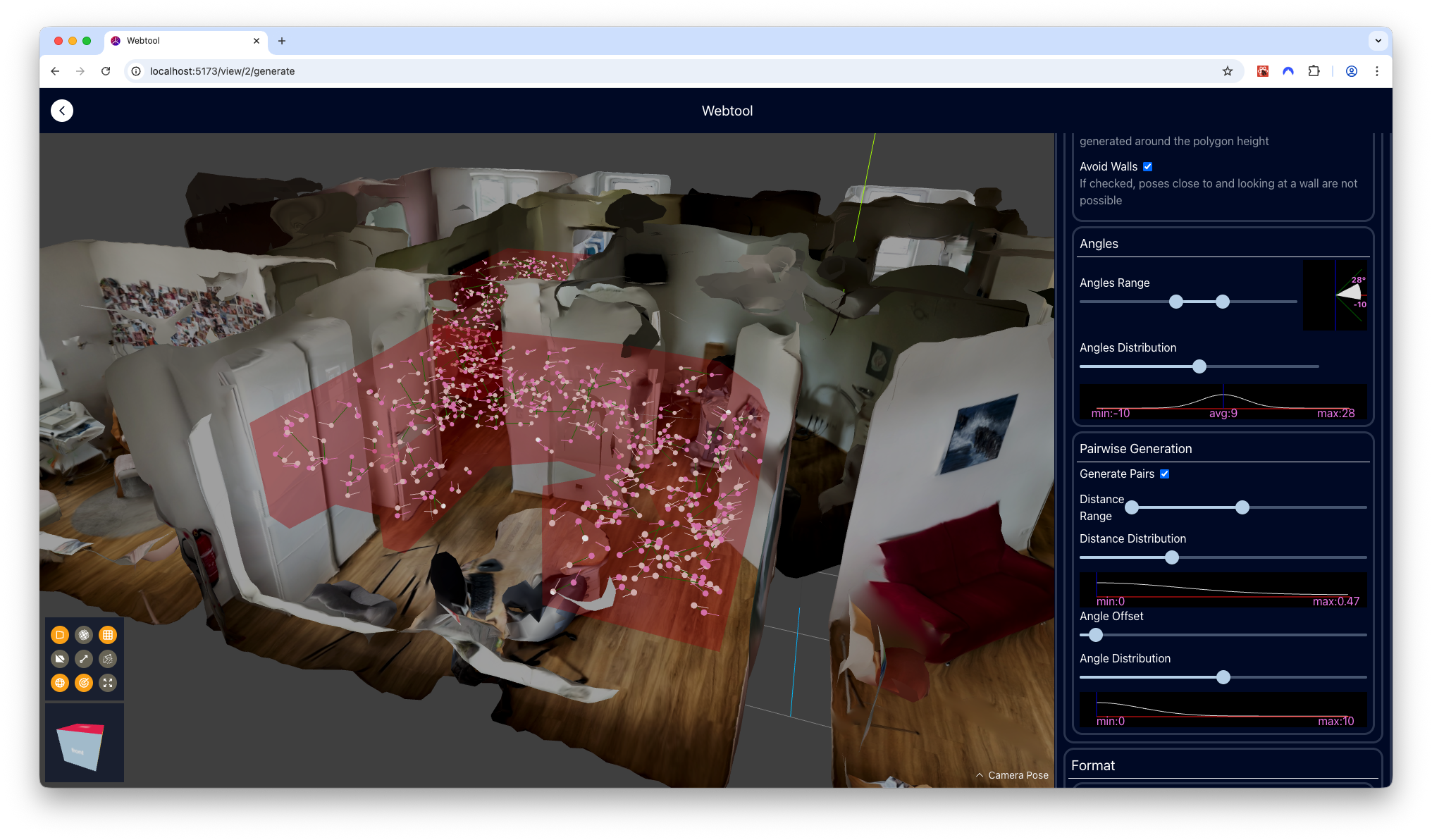

One area I spent much time and effort on was the usability of the web application - I wanted the app to be both intuitive for new users, and offer quick access to all features for experienced editors. Some features that facilitate this is the deliberate modelling of the typical editing workflow into the UI, which progressively unlocks tools from layout to pose generation stages. The usable tools and settings have an “expanded” mode that displays their names, and a “collapsed” mode that offers experienced users a greater usable viewport area. Whenever possible, numerical inputs and sliders are coupled with graphical “minipanels”, showing visualizations of how the chosen value will impact pose generation. Lastly, a maya-inspired “viewcube” was added to the viewport, which allows users to quickly assume orthographic viewing positions that are often used for defining areas.

Pose Generation: I developed a custom probability distribution that smoothly interpolates between uniform and concentrated sampling, giving fine control over parameters like possible camera height, pitch angles, and field of view. The system generates thousands of pose pairs (for odometry training) while avoiding unrealistic positions like facing directly at walls.

Texture Mapping: Since point clouds don’t include color information, I created a novel reprojection approach that uses the 360° images with known coordinates to color the mesh. The algorithm:

- Selects the nearest 360° images to each virtual camera position

- Uses shadow mapping to determine which 360° image has an unobstructed view of each surface point

- Combines contributions from multiple images to generate the final synthetic image

This reprojection is implemented in a fragment shader, thus vastly speeding up synthetic image generation.

I implemented several combination strategies that allow multiple 360° images to affect the shading of pixels in the output images: closest available, distance-weighted, and exponential weighting. Surprisingly, the simplest “closest available” approach worked best on our imperfect dataset, producing the most globally consistent images.

3. Neural Network Architecture

The network builds on VLocNet, a proven architecture for visual localization, with several key extensions:

MobileNet Foundation: Beyond the standard ResNet-50 base, I added support for MobileNet V3 Large, which uses 10× fewer parameters and runs 2.5× faster, allowing smartphone-based deployment.

Uncertainty Estimation: I added per-prediction confidence outputs, allowing the system to know when it’s uncertain and should fall back to other localization methods. This required modifications to the loss function to implement heteroscedastic uncertainty.

Post-training: Additionally, I implemented a fine-tuning phase using real 360° image crops that can be used to bridge the gap between synthetic and real images. However, evaluation showed this actually reduced generalization performance by causing overfitting to specific image locations.

Implementation Details

Mesh Reconstruction used a Python CLI tool leveraging Open3D and Trimesh libraries. To maintain responsiveness during long-running reconstruction operations, I implemented a threading wrapper that monitors for user interrupts.

The Web Tool was built with TypeScript, React, and Three.js, with Vite for fast iteration during development. Zustand handled global state management, while IndexedDB stored large assets like meshes and images. A key technical challenge was implementing the custom texture mapping in WebGL shaders, including packing both color and distance information for weighted interpolation into a single floating-point output using IEEE-754 format manipulation.

Network Training was implemented in PyTorch with support for distributed multi-GPU training. The codebase includes experiment management, automatic checkpointing, and comprehensive visualization of training progress and validation results. I ran training sessions in tmux to survive SSH disconnections.

Results

Testing on a 66×42 meter office building dataset produced encouraging results:

ResNet-based network: Median accuracy of 1.68m translation and 23° rotation MobileNet-based network: Median accuracy of 2.25m translation and 29° rotation

The mean errors were higher due to outlier predictions, but the median values show the network works reliably for most poses. Despite training exclusively on synthetic data, the network demonstrated stable performance on real test images captured by the robot but not used in training.

Several findings were counterintuitive:

- The simplest image combination strategy (closest available) outperformed more sophisticated weighted approaches on our dataset

- Additional fully-connected layers didn’t improve performance in this larger environment

- Pre-training individual network components (a technique from the original VLocNet paper) had no long-term benefit after full training

The uncertainty estimation proved effective, with a clear correlation between predicted confidence and actual localization error, particularly with an uncertainty penalty coefficient of 0.2.

Challenges

Data Quality: The 360° images from the robot contained small pose errors that needed manual correction before use. I implemented an interactive correction tool in the web application to address this.

Post-training Paradox: The fine-tuning procedure designed to adapt to real images actually hurt generalization by causing the network to memorize 360° image locations. This was evident in visualizations showing prediction clustering at training positions.

Takeaways

This project demonstrated that visual localization networks trained purely on synthetic data can achieve practical accuracy in real environments. The key insight is that existing robotic mapping data contains sufficient information to generate quality training data without manual collection.

The end-to-end pipeline—from point cloud to deployable network—shows promise for making indoor localization more accessible. While traditional approaches might achieve better accuracy with extensive infrastructure, this method offers a compelling trade-off between accuracy and deployment effort.

Future directions include collecting temporally independent test data to conclusively validate generalization, automating the 360° image calibration process, and investigating multi-floor performance. Integration with sparse infrastructure-based localization for difficult poses is another interesting avenue.